The local town council constructed the red soil road to prevent vehicles from getting bogged in the heavy sand leading up to the Charleville Aboriginal reserve. The reserve was known as the ‘Yumba’ (meaning camp) among its residents and it was situated on the outskirts of town, approximately three kilometres from the town centre. It was home to about 15 families, including mine. How generous the council was to build this road for us … after herding us off our land! Later, the strategically placed toilet blocks and water taps, also built by the council, made the living conditions on the camp slightly more bearable.

Two roads entered the camp: the top road, adjacent to the railway line, and the second road that turned off it, which became the red soil road. The top road was a nicely maintained gravel road and mainly used by the local council to access the animal pound. People also used it to agist their horses and other livestock. Mr Chapel, the pound keeper, lived at the end of the top road with his family. The families from the camp thought highly of the Chapels as they were very friendly towards us, and their hens provided a constant supply of freshly laid eggs. It was also the place where I had my first taste of ginger beer … It wasn’t the most pleasant of drinks but I managed to keep it down as I didn’t want to embarrass my big sister by spitting it out.

The second road extended on a farther kilometre before it eventually met up with the red soil road. The red soil road would then wind its way through relatively thick bushland that consisted mainly of cypress pines that were home to hundreds of happy jacks. There were clusters of red berry bushes, so pretty during their fruit-bearing season, full of tasty red berries that us kids would feast on, and the occasional monkey tree that hung lazily out over the road, all creating a pleasant welcome into our often volatile environment. The entrance was marked by a cluster of beautiful and majestic white gum trees, standing tall and strong on the left side of the narrow bush road. As I passed by, I would look up through the leaves and branches into a gloriously blue western sky; it gave me a real sense of homecoming.

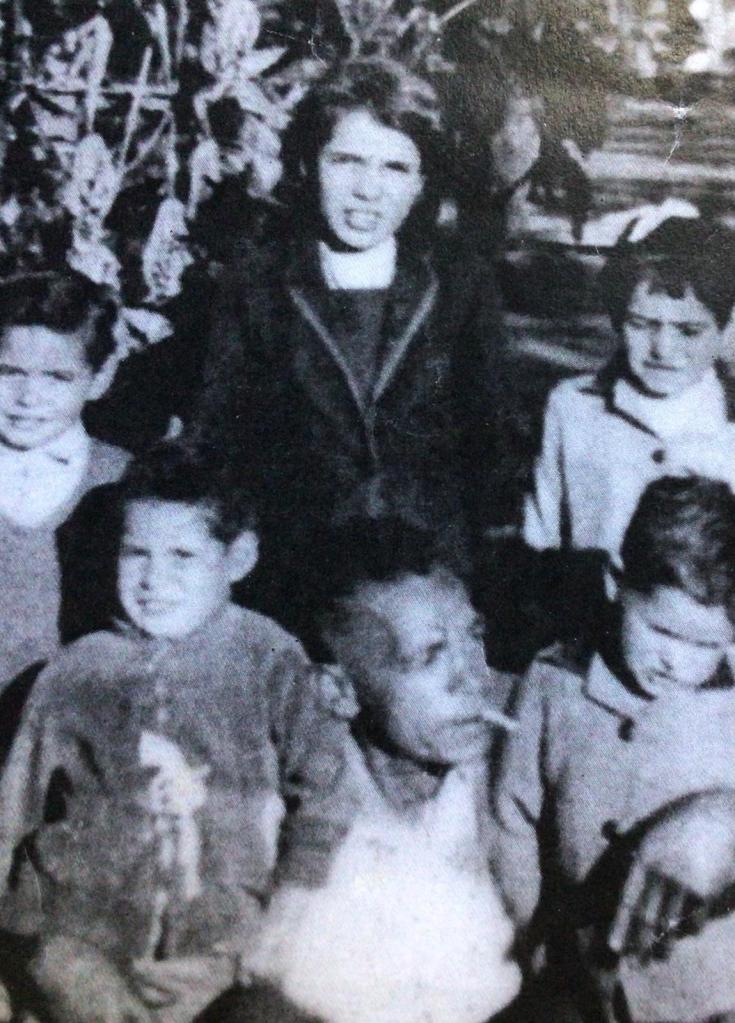

Joan, fondly nicknamed ‘Tonkie’, was my cousin. She lived with our grandmother, Sarah Mitchell, when her mother was out working as a domestic servant on sheep and cattle properties around the district. Tonkie was quite a reserved child and Granny adored her. I think she was her favourite. Tonkie had a beautiful big smile with pearly white teeth that beamed through her often cheeky smile. Her fuzzy jet-black hair was wild and beautiful. I remember watching Granny combing the knots out each morning, desperately trying to tame her curls. Granny took good care of Tonkie, who was always clothed immaculately in neatly washed and ironed dresses—Tonkie looked a picture as she and her sisters marched off along the red soil road to school uptown.

The red soil road was the main thoroughfare for traffic coming in and out of the reserve and most families built their shanty homes adjacent to the road for easy access to the toilet blocks and tap water. The toilet blocks were placed on the edge of the red soil road so that the pan collector could easily load them onto the back of his truck for disposal at the town’s sewer. The red soil road was our ‘Main Street’—all activities and community gatherings were held somewhere along the road. Brother Pickett would hold his Sunday school sessions under the big tree down near the Fraziers’ place and almost every kid on the Yumba would attend in the hope of getting something to eat (he was a very kind man and gave generously to the Aboriginal families). It was also the place I first learnt about Adam and Eve, and the first place I sang gospel songs. I loved sitting on the road with my cousins singing ‘Jesus Loves Me’ and many other beautiful songs, now only a faint memory.

Tomato Thomson, the town fruiterer, would visit each week in his little old horse-drawn sulky loaded with fruit and vegetables to sell. I remember one occasion when the bigger boys decided to ‘rob the stage coach’. We all gathered at the end of the red soil road where the sand was much softer, and we would build a speed bump in order to slow Tomato down. Once the bumps were built, we went and hid in the long grass so he couldn’t see us on his approach.

‘Here he comes!’ came the call from the tree above as the rest of us kids hid in the scrub. Bunny was the best tree climber so he was delegated the task of ‘spot and tell’.

‘These little black bastards are at it again,’ came Tomato’s anguished call as his old sulky came to a sudden stop. Out from the grass, us little black fellas would scamper to collect the goodies that the big boys were throwing out from the back of the old cart. We thought the ambush had been executed with great precision until the whip was drawn and the chase began. Sugar (later to become known as Sugar Ray Robinson) was our leader and we would follow him anywhere, but as Tomato got closer to us with his whip cracking, I was starting to wonder what kind of mess Sugar had gotten us into this time. I ran away as fast as I could! Bodge was the slowest of all and as we took off running with fruit and veggies in hand, we could hear him puffing and panting behind calling out for his older brothers to rescue him. ‘Gordon! Georgie! Gordon! Georgie!’ he called as he galloped towards home to the safe and protecting arms of Granny, his dear mother.

It seemed that Aboriginal people on the reserve needed to be saved, as many different religious groups preached the Bible to us. The Boskeys were one such group. Sure enough, they would be there every Thursday evening to save our souls. They would set up their music box and other musical instruments on the red soil road and start playing until almost everyone would wander over to listen and enjoy the entertainment. Everybody loved listening to the music and would clap their hands and sing along in tune until the sermon began. That’s when you would see the older men and women retreat into the darkness of night. I guess the Bible stories that the Boskeys told may have conflicted with their own knowledge and understanding of the beginning and ending of life … I never asked.

Living on the camp as a kid I was surrounded by loving, caring family and everyone shared what little we had, giving freely to each other, and as part of family I always felt safe except on one dreadful and horrifying evening. Most of the young men from the camp were out working this afternoon when a strange thing happened. Granny called all us kids inside her house and locked the door with a chain and padlock. To this day, I still can’t figure out how she knew what was about to take place shortly after locking us away. About four car loads of drunken hoodlums from uptown turned up yelling and screaming abusive language and throwing empty beer bottles at the house.

My granny, a Kooma woman, was small in stature but certainly not in courage as she stood outside her house on the side of the red soil road with stick in hand, ready to fight anyone who dared to enter the house where her precious grandchildren hid. We were so scared! Once the torment was over and everything returned to normal, it was time to feed her starving loved ones and naturally Granny served up a delicious meal, cooked in camp ovens on the outside fireplace.

On our return home to the Yumba from school, it was time to play. We would all change from our good second-hand clothes into our not-so-good second-hand clothes and off we would go looking for friends to play. I remember one day vividly. It was the day my cousin, Tonkie, invited me to feast on the red soil road. Yes, the red soil road! I knew food wasn’t so plentiful from my own experience growing up on the reserve, but to eat dirt was something I couldn’t comprehend.

Most afternoons, Tonkie and her friends would select a nice firm section of the road and begin digging under it with a stick. When they gained sufficient leverage, they would put both hands under the designated area, and gently lift it up to break off a nice firm chunk. Normally the dirt would break off in large chunks and then it would be broken down into bite-sized pieces ready for consumption. I went with her each afternoon for a few days and watched. On this particular day, I worked up enough courage to try a bit of the road.

‘Just place it on your tongue and suck it like you are eating a piece of chocolate,’ instructed Tonkie. So being a good boy and not wanting to disappoint my cousin, I did as she told me. Placing this beautifully selected piece of chocolate-shaped red dirt in my mouth, I began to suck as per the expert’s advice, but it wasn’t long before I started coughing and splattering. I took off for the nearest tap to rinse my mouth out.

‘What the hell? That’s disgusting! How on earth can you eat that stuff?’

‘Ahhh, ya don’t know what ya talking about!’ came her reply and she went on eating her delicious red soil. It would be just on dusk when Granny called the kids to come and have dinner; she wanted everyone fed before darkness set in. Tonkie would quickly gather up a collection of carefully chosen dirt for that night’s snack.

Later on in life, I often wondered why people on the reserve ate the red dirt and it wasn’t until the late Charles Perkins commissioned a study into the reason why kids in Alice Springs and central Australia sniffed petrol that I understood. The findings indicated that the youth were sniffing petrol to take away their hunger pains, and, as a result of that research, I concluded that must have also been the reason why so many people ate the red soil road.

Many years ago I had the good fortune of travelling to Africa with my three children. While in Johannesburg, my son and I took a day trip of the city and one memorable aspect of the trip was visiting Soweto. Soweto is a suburb of Johannesburg and home to approximately 4 million people, most famously Desmond Tutu and Nelson and Winnie Mandela. I was very surprised when our tour guide pointed out where they all lived in the same street. Later that night I was reflecting on the day’s outing and I thought about the enormous achievements of Tutu and Mandela and the difference they made in bringing about change; it made me think about the achievements that some people on the camp also made. While not nearly as extraordinary, what my parents, my cousin John Leslie and Sugar have done here in Queensland and Australia is worthy of note considering our upbringings.

My dad, the late Jack Martin, and Charlie Renouf from Murgon, were the first two Aboriginal legal service field officers in Queensland and tireless workers for their people. Zona Martin, my dad’s wife and my mother, was his strongest advocate and she stood by his side and supported him until his untimely death. Mum was awarded the National Aboriginal Elder of the Year at the National Aboriginal NAIDOC Awards in Alice Springs for the many years of voluntary work she did and was appointed an Aboriginal development commissioner to represent the voice of her constituents. My cousin, John Leslie, had his leg amputated after a train ran over him and he was shot with a rifle while living on the camp as a kid. John is a self-educated man who worked across many areas, seeking social justice for Aboriginal people and was most prominent in achieving his objectives as the chief executive officer of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service.

Sugar Ray Robinson was one of the first Aboriginal people to do a presentation at the United Nations in Geneva. He was elected as an ATSIC commissioner for a period of 12 years and has held high office in countless other organisations. I guess one can say that the little Aboriginal reserve that sat on the red soil road on the outskirts of Charleville was home for a while to some fairly well-known and inspirational people just like the Tutus and the Mandelas. And not withstanding my own small contributions, I was a member of the Queensland Land Tribunal that recommended to the state government the return of two areas of land to its traditional owners in North Queensland. I was one of only a handful of people elected to the ATSIC regional council for the length of its 15-year existence. And a member of the inaugural Queensland deaths in custody committee, which was established to oversee the implementation of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody recommendations.

The red soil road was a very important landscape for those who grew up on the reserve. It was more than a road that wound its way through the little settlement on the outskirts of town, our Yumba. It was many years later at the Charleville Yumba Reunion that you could feel a real sense of sadness in the hearts of the attendees because their beloved red soil road couldn’t be found. Years had passed and the shifting sands and overgrowth had taken their toll on the old road and now it is gone forever.

Just recently I was chatting with my cousin Tonkie. I told her that I had written a story about the red soil road and had included her in it. We joked about her eating the red soil and how she would keep a Sunshine milk tin of soil under her bed to snack on just in case she felt hungry during the night.

‘A woman needs her red soil like a man needs his red meat,’ I said to her with a wry smile on my face … She was very quick to remind me that her favourite spot to collect red soil, and the soil that suited her palate best, was outside Rollie Forbes’ shop on the Boatman Road.