Zona Merle Leslie, my mother, was born in the Moree hospital on the 17 May 1931 in the McMasters Ward.

Eric Leslie was my mother’s father and sadly I never had the pleasure of meeting him. A drover from Walhollow Mission in New South Wales, he was an excellent horseman and a man who worked tirelessly to make ends meet and support his family. Mum remembers him as a very kind and gentle man and she loved him dearly.

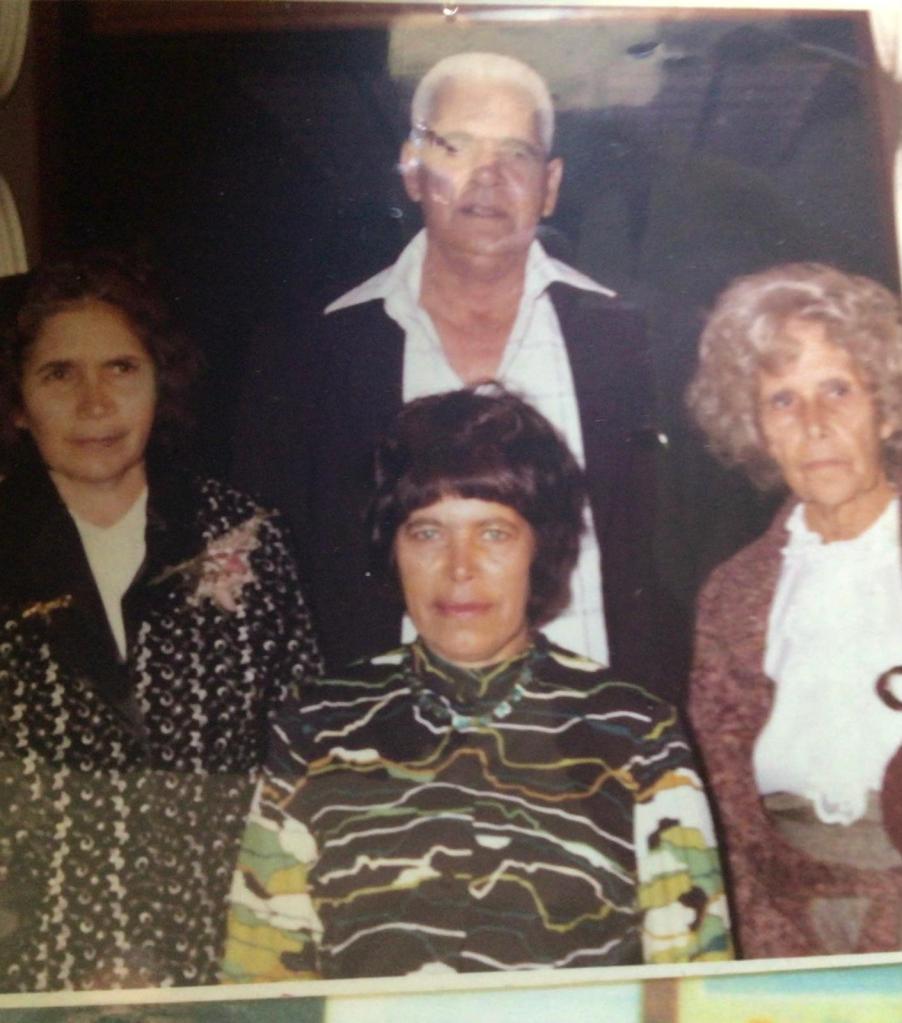

Nan Leslie lived with her daughter, my Auntie Barb, in Toowoomba towards the end of her life and she was confined to a wheelchair as she suffered with diabetes and had her leg amputated. She was a strikingly attractive woman, as I remember, with sharp features and beautiful hazel eyes. Her mother, Emily Beale, was from Breeza mission in New South Wales. Her children included Eric, Barbara, Laurence and Zona.

The McMasters Ward was separated from the main hospital – a hospital within a hospital, and it was established specifically to cater for the Aboriginal people, with its own nursing staff while doctors would be on call to attend when needed.

It was obvious from the stories Mum told us that she enjoyed living and growing up on the Moree Mission. The mission sat on the outskirts of Moree approximately four kilometres from the town centre and Mum’s family were the first ones to settle there. The mission land was set aside by the New South Wales government to accommodate the Koories from around the region who were forced from their traditional lands earlier to make way for the graziers.

After her dad passed away Nan Leslie would move her family closer to town into Sophie Row where they would live with her brother Raymond Smith. All the black kids from the Top Camp and Sophie Row would have to walk down to the mission school as they weren’t allowed to attend the white school in town.

Mum and her siblings would continue attending the mission school and they’d walk down each day from Sophie Row to school.

She shared many memories of her school days but one I remember was when, in her words, they ‘cleaned up the white kids’ at the inter school marching competition.

Miss Kinear was their teacher and Mum said she was so proud of her little black kids as they marched to the beat of the band all dressed in the uniforms that she’d made with her own hands. But they didn’t have the white sandshoes like all the other schools they marched barefooted.

The sandshoes must have looked sexy to mum somehow as she said she really wanted a pair, so the first thing she bought when she started work as a domestic at the Victoria Hotel in Moree was a pair of white sandshoes.

Mum described Miss Kinear as very gentle person with a kind and caring nature. Tall and thin of about forty years of age, she wasn’t married and lived with her sister and her kids near the golf course.

She spent many hours after school teaching the kids how to tap dance and sing for the end of term concerts.

It was some sixty years later when Mum was living in Toowoomba that her cousin Carmine Munro called and tell her that Miss Kinear was sick in the Moree hospital so Mum and Auntie Barb, Mum’s older sister, drove all that way to visit her.

Miss Kinear must have made an enormous impression on them to drive so far to visit her I thought. I can just see them cruising along, two old ladies, barely big enough to look out over the dashboard and chatting away with all the excitement of teenage girls and the thought of going back home to Moree.

I felt sorry for Auntie Barb when Mum told me about the time when the school inspector came to visit the mission school and he noticed that she was still there and in his opinion it was time for her to move on as she was now old enough to leave school. Where would she go and what would she do with herself now that her school days were over?

I can only imagine how confronting it would have been for her to be unexpectedly placed in that situation. So much for assimilation. ‘We owned the land and we knew it.’ That’s what Mum told me as she recalls the time when the soldiers would pass by their camp on their way to the rifle range.

‘All us black kids would race over to open the gate and let the army vehicles through,’ she would say. ‘But we’d only let them through when they paid – it was our land!’

She said the soldiers must have liked us kids because when they were leaving they’d throw us more coins.

I asked Mum if people around Moree spoke in their own language and if they practiced any traditional ways and with a look of bewilderment on her face she replied, ‘No.’

She remembers that the mission was home to many different tribal groups other than her own tribe, Kamilaroi, and she said that may have been the reason why no one practiced their culture.

I guess Mum and people of her generation just accepted that that’s the way it was, and never asked questions or challenged the reasons why they were forced into living on missions, and not being allowed into the public swimming pool or the uptown school.

Charles Perkins an Aboriginal man and a well-known public figure in Australian politics was instrumental in organising what was known as the ‘Freedom Ride’ back in the mid-sixties and one place they visited was the Moree swimming pool.